{:it}Era il 1839 e un giovane pittore tedesco ,Johann David Passavant , figlio di un commerciante di provincia, che aveva frequentato la scuola di Jacques-Louis David a Parigi e poi seguito i corsi dai mistici Nazareni a Roma, decide di recarsi a Urbino per scoprire qualcosa di più del suo artista preferito: Raffaello, di cui in seguito diventerà un grande e riconosciuto esperto.

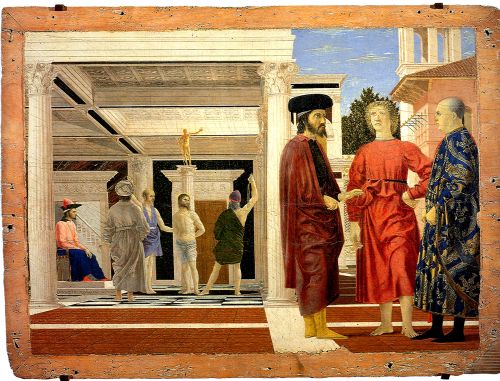

Come spesso accade,che quando cerchi una cosa ne trovi sempre un’altra, Passavant per caso viene a sapere che il padre di Raffaello aveva abitato un anno assieme a Piero de’ Franceschi, l’autore di quella piccola tavola semi abbandonata che scorge nel retro della sacrestia del Duomo di Urbino e di questa racconta: “ Rappresenta Cristo alla colonna davanti a Pilato. In primo piano si vedono tre gentiluomini, uno dei quali, vestito sfarzosamente di seta e oro, è dipinto alla maniera olandese.

Oggi la tavola de “ La Flagellazione” di Piero della Francesca si può ammirare nel Museo Nazionale delle Marche , nella cornice dello splendido palazzo ducale di Urbino, una delle meraviglie architettoniche italiane. Piero di Burgo, come veniva chiamato, è un autodidatta, concittadino e amico di Luca Pacioli, il francescano matematico autore della Divina Proporzione,ma anche di altri insigni matematici e filosofi. Egli studia e applica i dettami di Pitagora e Archimede per raggiungere la perfezione dei propri disegni. Verrà anche chiamato pittore e matematico: suo è il testo “ De prospectiva pingendi” dove redige un trattato sulla prospettiva albertiana e il “ Libellus de quinque corporibus regularibus” , un ostinato trattato sulla quadratura del cerchio, itinerario già percorso da Niccolò Cusano. Egli non è solo un pittore ma un intellettuale che studia lo spazio, un esoterico in cerca della pietra filosofale.

Un pittore intrigante, dunque. Di lui rimangono forse quindici o venti opere e sono sufficienti a farne un colosso della storia dell’arte, Piero è fondatore di una visione che rimane intimamente legata alla sua terra, che si estende tra Toscana, Umbria e Marche e si ferma ad Urbino dove abita uno dei suoi più importanti committenti: Federico da Montefeltro.Inizia qui la sua carriera sotto l’egida del suo mecenate, prototipo del principe di allora: aggressivo, sveglio, combattente, sicuro di sé al punto che si fa ritrarre con il famoso taglio del naso che gli permetteva di sbirciare a destra con l’unico occhio che gli era rimasto. Piero e Federico sono l’emblema della corte di Urbino, così diversa da quella di Firenze, dove c’è solo il potere del denaro in primis e dove si possono avere belle donne. Coltissimi i Medici ma ancora più colto è Federico da Montefeltro con la sua biblioteca seconda solo a quella del Vaticano e che con i suoi mezzi da mercenario – era uno dei più abili condottieri al soldo dei vari potentati – guadagnava fortissime somme che reinvestiva tutto nel suo ducato. Quello che rimane nel terra del Montefeltro oggi è davvero un capolavoro di abilità architettonica, pittorica, stilistica, artigiana.

Ma ritorniamo alla Flagellazione di Piero della Francesca, che non è solo un enigma è un vero e proprio rompicapo.

Molti storici dell’arte, nonché poliziotti veri, utilizzando le moderne tecniche investigative di riconoscimento dei volti, hanno dato la loro versione della tavola, la cui unità di misura è raffigurata nella striscia nera che vedete sopra la testa del uomo con la barba a punta in primo piano e cioè cm. 4,699. La tavola è sette volte per dieci questa unità.

Le varie interpretazioni provano a spiegare simbolicamente chi si nasconde dietro gli attori presenti in scena, chi sia Pilato seduto, o chi sia l’uomo in broccato dall’altra parte della tavola ma soprattutto chi rappresenti il giovane uomo biondo con la casacca rosso porpora – le vesti color porpora appartenevano solo ai re, alti prelati ed imperatori : ottenere questo colore era costosissimo, veniva usata la cocciniglia, questi poveri animaletti non erano poi così facili da trovare – e con i piedi nudi. Di alcuni il riconoscimento è più chiaro, gli uomini con la barba ad esempio sono greci, perché a quei tempi solo loro la portavano. Anche chi indossa il turbante è facilmente riconoscibile. Su tutti gli altri si scatenano le più possibili congetture di cui molte plausibili, specie quelle più recenti.

Esistono, anche su internet, differenti e avvincenti versioni della tavola e sui personaggi raffigurati. Per chi volesse avere un’idea più approfondita del periodo nel quale Piero è vissuto, uno dei più incredibili e affascinanti del nostro paese, vi consiglio la lettura del testo di Silvia Ronchey, “L’enigma di Piero”; lascia sorpresi e con un irrefrenabile desiderio di saperne ancora di più: sulla prospettiva,la divina proporzione, la quadratura del cerchio e ancora su Leon Battista Alberti e la sua “ De Re Architectura” , la filosofia in generale e su Platone in particolare, ma ancora di più sulla storia dei personaggi che vissero in questo straordinario e così fecondo periodo: Federico da Montefeltro, Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, Bessarione, la dinastia dei Paleologo, Mistrà, Giorgio Gemisto Pletone, Bisanzio, Venezia, Carpaccio, Manuzio , Marsilio Ficino, i Medici, Pio II, Cleopa Malatesta… la lista seguiterebbe ma mi fermo qui.

E’ stato un periodo esaltante e pieno di prospettive appunto, dove gli innumerevoli testi greci che venivano portati in Italia dagli esuli in fuga vennero consultati, ricopiati, protetti. Molti di questi finirono per costituire il patrimonio basico di magnifiche biblioteche come la Marciana a Venezia e la Laurentiana a Firenze.

E’ difficile riassumere in poche parole il senso di quest’opera senza rischiare di farne un vero polpettone pseudo romanzato che lascio a chi è più esperto di me, ribadisco solo che varrebbe la pena di lavorare su questo particolare periodo storico e di scriverci infiniti romanzi. Si ha la sensazione che il contenuto del suo messaggio, quanto di quei tempi i dotti hanno appreso e approfondito con lo studio dei testi greci , sia stato appena accennato, almeno in Italia, e che per varie ragion di Stato hanno poi preso percorsi differenti, lontani da qui.

Leopardi, a mio avviso, fù uno di quelli che in seguito più ne avvertì il vuoto.{:}{:en}

In 1839 a young German painter, Johann David Passavant, a provincial merchant’s son who had attended Jacques-Louis David’s school in Paris and then attended courses by the Nazarene mystics in Rome, moved to Urbino to discover something more about his favorite artist, whom later he would become a great and recognized expert: Raffaello.

As often happens, when you look for something, you always discover something else, Passavant by chance finds out that Raffaello’s father had lived a year together with Piero de’ Franceschi, the author of that small, semi-abandoned table that you can barely see in the back of the sacristy of the Duomo of Urbino, and he tells that it “represents Christ at the Column in front of Pilate. In the foreground there are three gentlemen, one of them, dressed in silk and gold, is painted in the Dutch way”.

Today the painting “Flagellation of Christ” by Piero della Francesca can be admired in the National Museum of the Marche, in the frame of the splendid ducal palace of Urbino, one of the Italian architectural wonders. Piero di Burgo, as he was called, is a self-taught, fellow-citizen and friend of Luca Pacioli, the mathematician Franciscan author of the Divine Proportion, but also of other mathematicians and philosophers. He studies and applies the dictates of Pythagoras and Archimedes to achieve the perfection of his designs. He was later also called a painter and mathematician: he wrote the text “De prospectiva pingendi” where he draws up a treatise on the “albertian perspective” and the “Libellus de quinque corporibus regularibus”, an obstinate treatise on quadrature of the circle, itinerary already run by Niccolò Cusano. He is not only a painter but an intellectual who studies space, an esoteric looking for philosopher’s stone.

An intriguing painter, then. There are perhaps fifteen or twenty works of his own and are enough to make him a giant of the history of Arts. Piero is the founder of a vision that remains intimately tied to his land, extending between Tuscany, Umbria and Marche and stops at Urbino where one of his most important customers lives: Federico da Montefeltro. Here begins his career under the patronage of his patron, prototype of the prince of then: aggressive, awake, fighter, self-assured to the point that he is portrayed with his famous nose that allowed him to peek right with the only eye that had remained. Piero and Federico are the emblem of the court of Urbino, so different from that of Florence, where there is only the power of money in the first place and where you can have beautiful women. The Medici are very cultured, but even more culturated is Federico da Montefeltro with his library second only to that of the Vatican and who with his mercenary means – he was one of the most skilled soldiers at the expense of the various potentates – earned very high sums that he reinvested all in his duchy. What remains in the land of Montefeltro today is truly a masterpiece of architectural, pictorial, stylistic, artisanship.

But let’s go back to the “Flagellation” by Piero della Francesca, which is not just an enigma, it is a real puzzle.

Many Arts critics, as well as real police officers – using modern face recognition investigative techniques – have given their version of the painting, whose unit of measure is depicted in the black strip that you see above the head of the bearded man in the foreground, ie 4.699 cm. The painting is seven times this unit.

The various interpretations try to symbolically explain who is hiding behind the characters in the scene, who is Pilate sitting, or who is the man in brocade on the other side of the painting but above all who represents the young blond man with the purple scarf – the purple garments belonged only to kings, high priests and emperors: getting this color was very expensive, the coquette was used, these poor little animals were not so easy to find – and with their bare feet. Of some characters, recognition is easier, for example, bearded men are Greeks, because at that time they were the only ones wearing it. Even those wearing turbans are easily recognizable. On all others, the most likely guesses are made, of which many are plausible, especially the most recent ones.

There are also on the internet different and fascinating versions of the painting and its depicted characters. For those who want to have a more in-depth idea of Piero’s life, one of the most incredible and fascinating of our country, I recommend reading Silvia Ronchey’s text “L’enigma di Piero”. We are surprised and with an irrepressible desire to know even more: about perspective, the divine proportion, quadrature of the circle and again on Leon Battista Alberti and his “De Re Architectura”, philosophy in general and on Plato in particular but even more on the story of the characters who lived in this extraordinary and so fertile period (Federico da Montefeltro, Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, Bessarione, the dynasty Paleologo, Mistrà, Giorgio Gemisto Pletone, Bisanzio, Venice, Carpaccio, Manuzio, Marsilio Ficino, Medici, Pius II, Cleopa Malatesta … the list would be longer).

It was a time of excitement and full of prospects, where the countless Greek texts that were brought to Italy by escaping exiles were consulted, copied, protected. Many of these ended up creating the basics of magnificent libraries such as Marciana in Venice and Laurentiana in Florence.

It is difficult to summarize in a few words the meaning of this work without risking of making it a true pseudo-fiction meatball that I leave to those who are more experienced than I am, I just repeat that it is worth working on this particular historical period and writing endless novels. It is felt that the contents of his message, as learned from the times learned by Greek scholars, has just been mentioned, at least in Italy, and that for various reasons have then taken different paths, far from here.

Leopardi, in my opinion, was one of those who later became aware of this void.{:}